Sometimes, a person is born who, for the well-being of others, will sacrifice what we generally consider our sacred right: putting one’s own pleasures and wishes first. Sadly, it happens so seldom that such people’s input doesn’t bring fundamental change to the world. It is, after all, only one life.

Reading the book about Susan La Flesche made me think that a single life might be enough. Not to alter how the world works, but to highlight the importance of not giving up. Even though it might seem that her battles were for naught, it isn’t so. True, Susan La Flesche had not saved her people from serious diseases and alcoholism. Neither had she prevented them from selling ninety percent of the land allotments they had finally been allowed to have as their rightful property. What Susan La Flesche had done was set an example of determination and perseverance. Who knows, maybe it can inspire others to follow in her steps.

Have you heard of Susan La Flesche? I hadn’t known anything about her before reading this book. And she was an incredible woman.

First of all, she was the first female Native American medical doctor. She received formal medical education, something not so many white women had access to at the time.

Next, she worked relentlessly and selfishly to improve the lives of her tribe. Not only had she been the only doctor in the Omaha tribe for years, having over a thousand patients scattered across a huge reservation territory, but she also advocated for improvements in other spheres of the tribe’s life, using her connections.

Susan La Flesche wasn’t just a simple girl from the Omaha tribe. Both her parents, along with Indian, had white ancestry. But both had chosen Omaha as their cultural identity. Moreover, Susan’s father was the Omaha tribe leader. He was pragmatic in terms of accepting the white man’s dominance and the laws of the American government. Not all of Omaha agreed with him, and not all of them later agreed with Susan, who continued her father’s crusade against alcohol and promoted integration.

Susan used her connections to bring the problems of the Omaha to the decision-makers’ attention. She was relentless in sending letters to those in charge of the reservation, her friends with influence, anyone she could reach in the government, describing the issues that complicated life in the reservation. Her noble zeal came at a cost. Over the decades, while she cared for her patients and advocated for her people to have equal rights with white Americans, her health, after an alarming episode already in her youth, continued to decline, keeping her bedridden and suffering from painful symptoms for months. Every time, though, once she recovered, she returned to the enduring hours tending to the sick and fighting for the rights of the Omaha.

It did enter my mind if the sacrifice was worth it. The Omaha seemed to take Susan La Flesche for granted. She was the first to whom they ran for help and the last to whom they listened when she urged them to be careful with alcohol and their property. I don’t have an answer to the question of whether her people deserved her. I believe that to find it, one has to have a wider perspective than any mortal human being can have. What I can claim with certainty is that I admire this woman. Indifference can never cause admiration. Even if it proves to be beneficial for the one who exploited it. I also think that Susan had deliberately chosen the path of sacrifice, hard work, and seemingly futile efforts. Whether it was her nature or caused by the heightened sense of gratitude and responsibility for all the unique chances she had received in terms of education and connections, I have no way of knowing. But from what I could deduce from the book, I’m inclined to believe that the latter is possible.

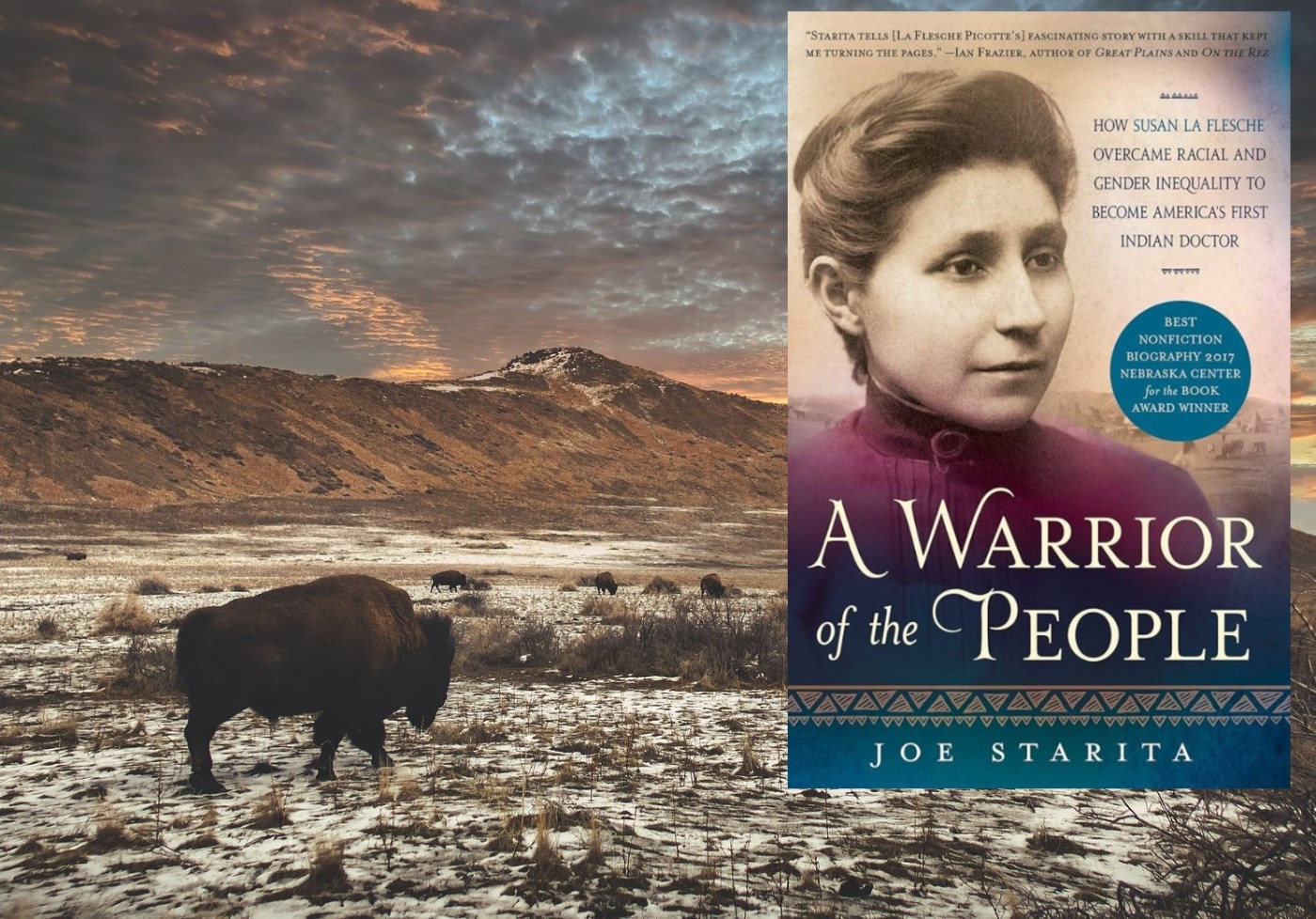

All in all, I loved this book, “A Warrior of the People: How Susan La Flesche Overcame Racial and Gender Inequality to Become America’s First Indian Doctor” by Joe Starita. It was very educational and also inspiring. I had a feeling, though, that the author overdid it trying to add a sensational quality to the narrative, as it’s often done in books intended for a wide audience. Also, chapters were often finished with a theatrical flourish. While I understand the reasoning behind choosing such an approach, it didn’t work for me, which, of course, is strictly subjective. If anything, it diverted my attention from the story, engrossing without artificial embellishments.

I always find your reviews edifying as you point out the strengths and also the needs of the text. I too find contrivance doesn’t work, but for some, it is very appealing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for reading, Anne!

Yes, what doesn’t work for us works perfectly for other readers, who need to be constantly ‘pushed’ to turn the pages. It’s not a bad thing. It’s just that we all have different preferences.

LikeLiked by 1 person